AI Tutorial: Understanding the basics of TensorFlow Lite MCU

Abstract

Writing raw CMSIS-NN code (C) manually is difficult and error-prone. Instead, the industry standard is to use an Inference Engine that calls these optimized kernels for us. In this lab, we will use one of several TensorFlow Lite for Microcontrollers (TFLM) API available to deploy a Keras model (model.h5) onto an STM32 board to estimate the sine value.

1. Introduction: The "Hello World" of Embedded AI

1.1 From Theory to Practice

In the previous entry of our Embedded AI Series, we defined the landscape of AIoT and explored the theoretical architecture of TinyML. We discussed how moving intelligence to the edge saves bandwidth, reduces latency, and protects privacy. But theory alone does not blink an LED or so to speak.

Now, we transition from the whiteboard to the IDE. This article represents Lab 1, your first hands-on encounter with the TinyML deployment pipeline.

1.2 Why a Sine Wave?

You might be asking: “Why are we predicting a sine wave? Why not jump straight to voice recognition or vibration analysis?”

In standard programming, we write printf(“Hello World”); not to demonstrate complex logic, but to prove that the compiler, linker, and hardware drivers are functioning correctly. In TinyML, the Sine Wave predictor is our “Hello World.”

Training a model to replicate the function $y = \sin(x)$ allows us to verify the entire end-to-end workflow without the noise and complexity of messy physical sensors. It confirms three critical things:

- The Toolchain: Your Python environment can train a model that your C++ environment can read.

- The Math: The Neural Network is converging and learning a pattern.

- The Hardware: The microcontroller can execute the inference engine within its memory constraints.

1.3 What You Will Build

In this lab, we will strip away the magic. You will start by training a simple neural network in Python using TensorFlow. You will then perform Quantization—compressing the model from heavy 32-bit floats to lightweight 8-bit integers. Finally, you will deploy this model onto any Arduino board, including STM32 (or compatible Arm Cortex-M) device using the TensorFlow Lite for Microcontrollers (TFLM) library, enabling your chip to “dream” a sine wave in real-time.

2. Prerequisites

- Hardware: Arduino, STM32 board or Raspberry Pi Pico. Any Arm Cortex board can be used for this “hello world”

- Software: Arduino IDE.

- Files: The model.h provided> ArduTFLite/examples/ArduTFLite_hello_world/model.h at main · spaziochirale/ArduTFLite

3. Step 1: Quantization & Conversion (Python)

Aside from this lab, where the model is already provided as a C file, the usual condition is to have the model in a high-precision floating-point format (32-bit). To run efficient inference on the most MCUs using CMSIS-NN, we must Quantize it to 8-bit integers (int8).

Run this Python script on your PC to convert your model.h5 into a C header file (model.h).

import tensorflow as tf

import numpy as np

# 1. Load your Keras model

model = tf.keras.models.load_model('model.h5')

# 2. Create the TFLite Converter

converter = tf.lite.TFLiteConverter.from_keras_model(model)

# 3. Apply Optimization (Quantization)

# This forces the model to use 8-bit integers, enabling CMSIS-NN acceleration.

def representative_dataset_gen():

for _ in range(100):

# Create dummy data matching your input shape (26 samples, 3 axes)

data = np.random.rand(1, 26, 3).astype(np.float32)

yield [data]

converter.optimizations = [tf.lite.Optimize.DEFAULT]

converter.representative_dataset = representative_dataset_gen

converter.target_spec.supported_ops = [tf.lite.OpsSet.TFLITE_BUILTINS_INT8]

converter.inference_input_type = tf.int8

converter.inference_output_type = tf.int8

tflite_model = converter.convert()

# 4. Save as C-Header

with open('model.h', 'w') as f:

f.write("const unsigned char model_tflite[] = {\n")

for i, val in enumerate(tflite_model):

f.write(f"0x{val:02x}, ")

if (i+1) % 12 == 0: f.write("\n")

f.write("\n};\n")

f.write(f"const int model_tflite_len = {len(tflite_model)};")

print("Conversion Complete. 'model.h' created.")

Recommendation

Most of the models made for embedded applications targetting MCUs can run on notebook and Google Colab: colab.google can be used to quickly implement, evaluate and convert to C.

4. Step 2: The Arduino Sketch

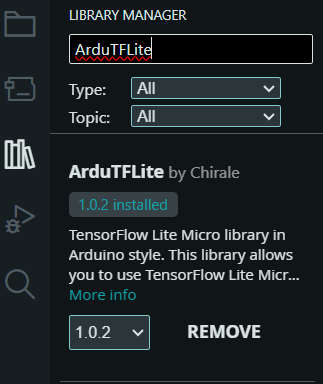

Open Arduino IDE and install the following libraries via the Library Manager:

- ArduTFLite

- Don’t use the Arduino_TensorFlowLite, this has been removed. If you have a legacy code, follow this minor tutorial to install this library: tensorflow/tflite-micro-arduino-examples

Create a new sketch, create a tab named model.h, and paste the output from Step 1 into it. Then, paste the following code into your main .ino file.

While TensorFlow Lite for Microcontrollers (TFLM) acts as an “Interpreter” (loading the model graph and deciding which functions to run), using CMSIS-NN directly requires you to act as the “Compiler” manually writing the C code to call each layer’s mathematical function in sequence.

Using CMSIS-NN directly is feasible and effectively removes the “Interpreter” overhead, saving you ~5-10KB of Flash and some RAM. However, because TFLM already uses CMSIS-NN under the hood, you will not see a speed increase, only a memory savings.

For a learning exercise or extreme optimization, it is an excellent challenge. For a production product where the model might change (e.g., retraining for better accuracy), sticking with TFLM or X-CUBE-AI is highly recommended to avoid the maintenance nightmare of manually updating C arrays.

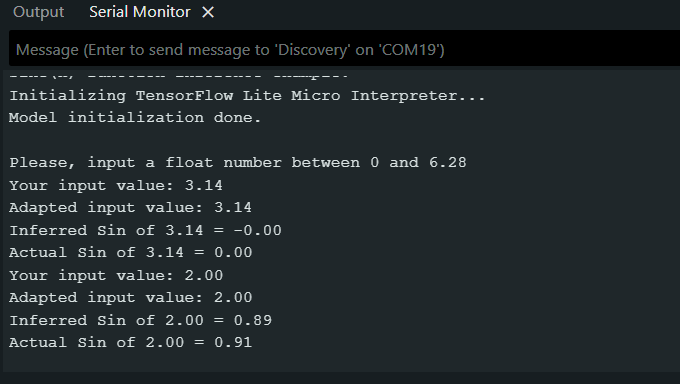

Here is the code using TFLM, using the equivalent to the “hello world” for embedded AI, a sine wave model:

// include main library header file

#include <ArduTFLite.h>

// include static array definition of pre-trained model

#include "model.h"

// The Tensor Arena memory area is used by TensorFlow Lite to store input, output and intermediate tensors

// It must be defined as a global array of byte (or u_int8 which is the same type on Arduino)

// The Tensor Arena size must be defined by trials and errors. We use here a quite large value.

// The alignas(16) directive is used to ensure that the array is aligned on a 16-byte boundary,

// this is important for performance and to prevent some issues on ARM microcontroller architectures.

constexpr int kTensorArenaSize = 2000;

alignas(16) uint8_t tensor_arena[kTensorArenaSize];

void setup() {

// Initialize serial communications and wait for Serial Monitor to be opened

Serial.begin(115200);

while(!Serial);

Serial.println("Sine(x) function inference example.");

Serial.println("Initializing TensorFlow Lite Micro Interpreter...");

if (!modelInit(model, tensor_arena, kTensorArenaSize)){

Serial.println("Model initialization failed!");

while(true);

}

Serial.println("Model initialization done.");

Serial.println("");

Serial.println("Please, input a float number between 0 and 6.28");

}

void loop() {

// Check if a value was sent from Serial Monitor

// if so, 'sanitize' the input and perform inference

if (Serial.available()){

String inputValue = Serial.readString();

float x = inputValue.toFloat(); // evaluates to zero if the user input is not a valid number

Serial.print("Your input value: ");

Serial.println(x);

// The model was trained in range 0 to 2*Pi

// if the value provided by user is not in this range

// the value is corrected substituting edge values

if (x<0) x = 0;

if (x >6.28) x = 6.28;

Serial.print("Adapted input value: ");

Serial.println(x);

// Place the value in the model's input tensor

modelSetInput(x,0);

// Run inference, and report if an error occurs

if(!modelRunInference()){

Serial.println("RunInference Failed!");

return;

}

// Obtain the output from model's output tensor

float y = modelGetOutput(0);

Serial.print("Inferred Sin of ");

Serial.print(x);

Serial.print(" = ");

Serial.println(y,2);

Serial.print("Actual Sin of ");

Serial.print(x);

Serial.print(" = ");

Serial.println(sin(x),2);

}

}

Understanding the Code

This sketch relies on the ArduTFLite library, which acts as a wrapper to simplify the complex TensorFlow Lite C++ API. Here is what is happening step-by-step:

- The Tensor Arena (tensor_arena): Unlike standard C++ where you malloc memory on the fly, TinyML requires a pre-allocated “sandbox.” constexpr int kTensorArenaSize = 2000; This reserves 2KB of RAM. All model weights, inputs, and intermediate calculations happen inside this array. If your model crashes or prints “Arena too small,” you must increase this number.

- alignas(16): This is a hardware requirement. The ARM processor processes data much faster when memory addresses are multiples of 16. If you forget this, the CMSIS-NN kernels might fail or run slowly.

- modelInit(): This function parses the model_tflite hex array you created in Python. It maps the model’s structure onto the Tensor Arena.

- modelSetInput(x, 0): TFLite models expect data in specific “tensors.” This function takes your float value x and places it into the input tensor (Index 0). Crucially, it handles the quantization automatically, converting your float 3.14 into the corresponding int8 integer that the model understands.

- modelGetOutput(0): After inference, the result is an integer inside the arena. This function retrieves it and de-quantizes it back into a readable float so you can print it to the Serial Monitor.

Here is the simplified demo usage:

5. The "Hidden" Optimization

You might wonder: “Where is the CMSIS-NN code?”

That is the beauty of the ecosystem. Because you are compiling for an ARM MCU (STM32, Raspberry Pi Pico) and using the TensorFlowLite library, the compiler automatically links against the optimized CMSIS-NN kernels.

However, to truly understand Embedded AI, let’s look at what is happening under the hood. Since we are predicting a Sine Wave, your model likely consists of Fully Connected (Dense) layers rather than Convolutions.

Here is how you would implement that manually, effectively writing your own Inference Engine.

- The Concept: Matrix Multiplication

Instead of loading a generic .tflite file, a manual implementation implies writing a C function that hard-codes the network architecture. For a Sine model, it looks like this:

void run_inference(int8_t* input_data, int8_t* output_data) {

// Layer 1: Fully Connected (Input -> Hidden Layer)

arm_fully_connected_s8(..., input_data, ...);

// Layer 2: Activation (ReLU)

arm_relu_q7(..., activation_buffer, ...);

// Layer 3: Fully Connected (Hidden Layer -> Output)

arm_fully_connected_s8(..., output_data, ...);

}

- The Implementation: Calling arm_fully_connected_s8

In the previous HAR example, we looked at Convolutions. For this Sine wave, we use Fully Connected layers. This is essentially multiplying the input vector by a weight matrix.

Here is the actual CMSIS-NN code required to run one single layer of your Sine model manually.

Step A: Define the Extracted Data You would need to extract these specific arrays from your model using a Python script (as discussed in the Lab) and paste them into your C code.

#include "arm_nnfunctions.h"

// Weights and Biases extracted from Python

const int8_t layer1_weights[] = { ... }; // Large array of trained weights

const int32_t layer1_bias[] = { ... }; // Bias values

// Quantization Multipliers (The "Magic" numbers)

// These convert the 32-bit internal math back down to 8-bit for the next layer

const int32_t output_mult = 12345;

const int32_t output_shift = -7;

Step B: The Execution Code This single function call replaces the generic interpreter->Invoke() for this specific layer.

// Dimensions

#define INPUT_DIM 1 // We only have 1 input (x)

#define OUTPUT_DIM 16 // Suppose we have 16 neurons in the hidden layer

#define BATCH_SIZE 1

// Context Buffer (Scratchpad memory for the math)

int16_t vec_buffer[OUTPUT_DIM];

void run_layer_1(const int8_t* input_data, int8_t* output_data) {

cmsis_nn_context ctx;

ctx.buf = NULL; // FC layers usually don't need extra scratch memory

ctx.size = 0;

cmsis_nn_fc_params fc_params;

fc_params.input_offset = 128; // Shifts int8 range (0-255 vs -128-127)

fc_params.filter_offset = 0;

fc_params.output_offset = -128;

// Activation Limits (Simulating ReLU)

fc_params.activation.min = -128;

fc_params.activation.max = 127;

cmsis_nn_per_tensor_quant_params quant_params;

quant_params.multiplier = output_mult;

quant_params.shift = output_shift;

cmsis_nn_dims input_dims = {BATCH_SIZE, 1, 1, INPUT_DIM};

cmsis_nn_dims filter_dims = {BATCH_SIZE, 1, 1, OUTPUT_DIM}; // Weights shape

cmsis_nn_dims bias_dims = {BATCH_SIZE, 1, 1, OUTPUT_DIM};

cmsis_nn_dims output_dims = {BATCH_SIZE, 1, 1, OUTPUT_DIM};

// THE KERNEL CALL

arm_status status = arm_fully_connected_s8(

&ctx,

&fc_params,

&quant_params,

&input_dims,

input_data,

&filter_dims,

layer1_weights,

&bias_dims,

layer1_bias,

&output_dims,

output_data

);

if (status != ARM_CMSIS_NN_SUCCESS) {

// Handle Math Error

}

}

Why does this matter?

Looking at the code above, you can see why we use TensorFlow Lite for Microcontrollers.

To write the code above manually, you must manage offsets, shifts, multipliers, and buffer sizes yourself. TFLM does all of this automatically. It reads the header file, calculates the multipliers, and calls arm_fully_connected_s8 for you.

However, understanding that this is the code running at the bottom of the stack helps you write better models. You know now that every neuron you add requires memory for weights and cycles for the fully_connected function.

6. Key Takeaways & Next Steps

6.1 The Pipeline is Universal

Congratulations! You have successfully deployed your first Neural Network onto a microcontroller. While predicting a sine wave may seem trivial, the workflow you just executed is identical to the one used for complex industrial applications.

Whether you are detecting a “fan failure” or recognizing the keyword “Alexa,” the steps remain the same:

- Train in high-level Python (Keras/TensorFlow).

- Quantize to fit the constraints of the edge (Int8).

- Convert to a C-array (Hex dump).

- Interpret on-device using an inference engine (TFLM).

6.2 The Power of Abstraction (and its limits)

In the final section of this lab, we peeled back the layers of the ArduTFLite library. We learned that TFLM is essentially a manager that organizes memory (tensor_arena) and calls highly optimized math kernels (CMSIS-NN).

Understanding this distinction is vital. For 90% of projects, you will use the high-level TFLM library. However, knowing that matrix multiplication (arm_fully_connected_s8) drives the system empowers you to debug memory overflows and understand why adding “just one more layer” might crash your chip.

6.3 What’s Next?

Now that we have verified our toolchain with a virtual data source (the Sine Wave), it is time to introduce the real world.

In Lab 2, we will ditch the generated data. We will connect a physical sensor—an Accelerometer (IMU)—and collect real vibration data. We will teach our microcontroller to recognize physical gestures, moving from “Hello World” to a truly interactive AIoT device.